Stoic philosophers have a practice called negative visualization. You imagine you are going to lose something or somebody. There are two reasons to do this. First, it may make a loss less painful; and second, you’ll appreciate that thing or person. This is great advice for anyone.

The Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote, “We should love all of our dear ones … but always with the thought that we have no promise that we may keep them forever – nay, no promise even that we may keep them for long.”

For months after my mom’s death, I was terrified of losing my father. I had nightmares about it. That fear of losing my dad was seared into my brain. Without knowing it, unintentionally and unwantedly, I was doing negative visualization.

I hate finding a silver lining in my mom’s death, but there was one. Losing my mother brought me closer to my father, not just in the months that followed her death but for decades, right up to the present. I lived with him until I got married in my late 20s. In my 30s and 40s I made sure to see him at least a few times a week. We’d go for morning walks. I stopped in for breakfast several times a week. A few times a year we’d go on trips, at first just the two of us (including to South Africa and Europe) and later with my kids. Our relationship is much deeper than just father and son; we are friends.

Imagining losing my father (negative visualization), right after I lost my mother, made me appreciate my father so much. My dad and I also got closer after Mom’s death because he had to come out of the academic bubble that Mom had allowed him to live in, instead of sharing parenting responsibility with her. I was his sole responsibility now. My brothers, who were both cadets at the Marine Academy, required a lot less care than me.

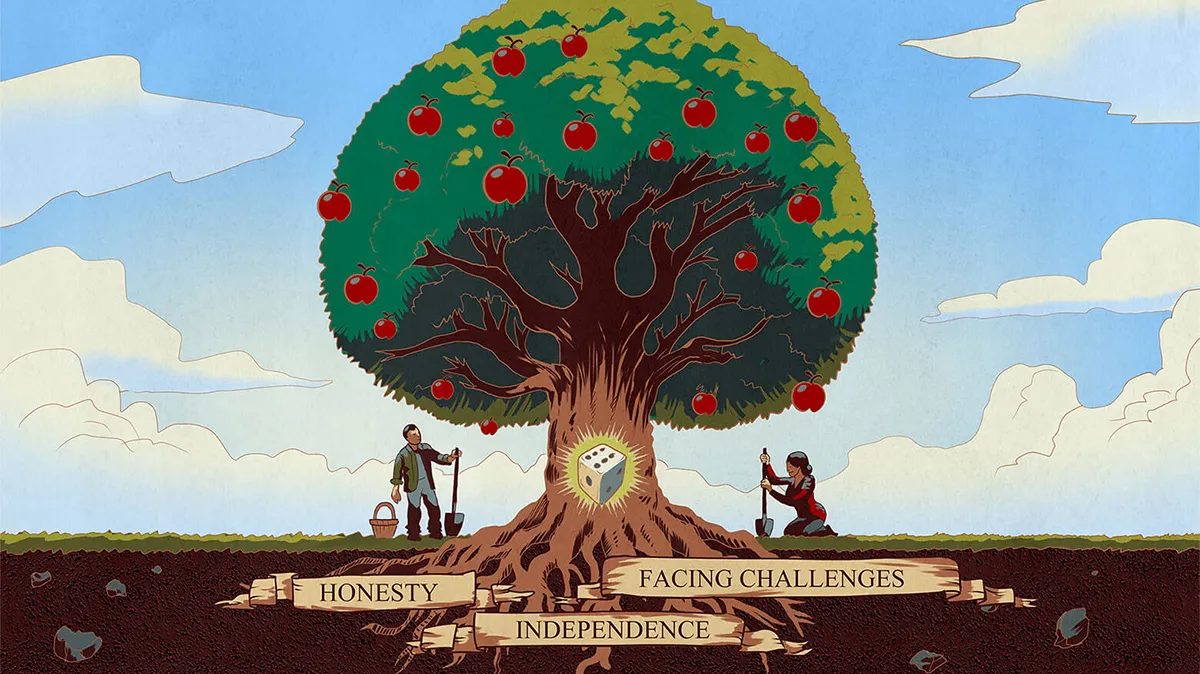

My father rose to the occasion of being a single parent. I was a light-hearted kid, but I was also lazy and lacked the ambition to study. My teachers decided I was not a good student, and I didn’t want to prove them wrong. My father had difficult material to work with, and he did the best he could. He also believed in me and always showed it, and eventually that belief paid off. (I am not congratulating myself here for lifetime achievements, but I have exceeded the very low bar I set for myself when I was a kid.)

When I face a difficult situation or when I evaluate my behaviour, I ask myself, what would my father do? My father is and always will be my role model. He is a role model not just of his intelligence, kindness, calmness, patience, and constant curiosity to learn, but for his bravery as well.

Our apartment in Russia was on the fifth floor. A family with eight children lived directly below us. My father jokingly called them the “garlics.” All their kids, like garlic cloves, looked the same; we could never tell them apart.

One day when I was 13, I came home from school for lunch. On my way back to school, as I was coming down the stairs, I smelled smoke coming from the garlics’ door. I rang the bell; I knocked; no one answered. I ran back upstairs and got a hammer, went back down, and started hitting the door, trying to open it. My father came down a minute after me, realized the situation, and quietly and decisively moved me aside. He told me to go to our apartment and call the fire department. He rammed the door open and walked into an apartment engulfed in fire. He went into every room and finally brought out two kids (five and seven years old). They were scared to come out from hiding under a blanket in their bedroom. If he had waited for the fire department, the kids could have burned to death or suffocated from the smoke.

At a school ceremony staged by the fire department, I was given a watch with the inscription, “For saving kids in a fire.” I had done absolutely nothing other than be at the right place at the right time and call the fire department. My father, on the other hand, had risked his life.

That was 30-plus years ago. You won’t see my father’s medal anywhere in his house. (I don’t think I’ve seen it in 30 years.) He never told this story to any of his friends. He is a person who is so comfortable with himself that he doesn’t seek external approval and is thus naturally modest.

A few years later after Mom’s death, my father married my stepmother, Feyga, whose son Igor is as close to me as my brothers are.

Not military material

Murmansk revolves around its port, and its academic institutions are geared toward producing a workforce for the fishing and merchant marine industries. It was always assumed that I’d attend either the Marine College or the Marine Academy. Both were semi-military schools where the students (cadets) had to reside in dormitories, wear navy uniforms, follow strict military-like rules, and take orders from navy officers (and ask no questions).

Russia had a draft army. It was not concerned about recruitment and thus treated its soldiers very poorly (an understatement). The pay was only high enough for soldiers to afford the postage to write home asking for money. Russian youth looked at serving in the Russian army as akin to a two-year prison sentence (at least when I was there; I have been told that has changed). Army avoidance in the late 1980s was not about fear of death, as the war in Afghanistan was over, but stemmed from the dread of losing years of one’s youth and the dismay of humiliation, as the older soldiers commonly abused the younger ones. A very sane friend of mine entered a psychiatric institution and faked mental disease just to avoid serving in the army.

My father and both of my older brothers graduated from the Murmansk Marine Academy. My father taught at the academy for 27 years. Neither my brothers nor I had any dreams about being seamen. Quite to the contrary, Leo could have been a philosopher (now he is an engineer). Alex wanted to be anything but an electrical engineer (he is now a successful real estate broker in Denver and has gone back to his art roots and become a terrific artist too). Our choices were limited: Either attend one of these two semi-military schools or join the Red Army.

By the time I finished eighth grade (the equivalent of tenth grade in the US), the law had changed: Cadets from the Marine Academy lost their draft exemption, but college cadets were spared. I enrolled in the Marine College and dreaded every moment I spent there. I lived in an army-like barracks, and wore a navy uniform. I hated taking orders from commanding officers and had no interest in the subjects I studied, but the alternative was even worse. This is what you do when you have few choices; you take the least poisonous alternative.

My aunt in Siberia

My father has two younger sisters. One lived all her life in Moscow, while the other moved with her family from Moscow to Siberia in 1979. For a long time, I wondered why my aunt and my cousins in Siberia never visited or called us. It seemed so uncharacteristic of our family, who were always very close. In the summer of 1988, my father finally told me that my aunt had not really moved to Siberia; she had emigrated to the United States of America. My immediate reaction was resentment. The first words out of my mouth were “traitor” and “spy.”

It sounds a bit silly now, but you have to understand that I was a child of the Cold War. A couple of times a month my class walked to the movie theatre (this was before VCRs) and watched propaganda documentaries about decaying capitalistic America, infested with the homeless, where black people were lynched, the poor were exploited by the rich, and people were poisoned by hamburgers (later, of course, I learned that the part about hamburgers was not a complete lie).

Russian movies showed Americans as evildoers, usually spies whose single goal in life was to destroy Mother Russia – the whole country was brainwashed. When I was nine years old, I attended a Pioneer camp and went on a field trip. A foreign tourist, mesmerized by my smile and internal beauty (okay, that is just a wild guess), gave me bubble gum. My camp teacher, in horror, took it away, yelling that I was lucky to be alive, as it was probably poisoned.

My father was not at all surprised to hear the words “traitor” and “spy” come out of my mouth. He calmly explained that despite being well educated, his sister’s family had lived in poverty because they had faced the invisible anti-Semitic wall that is so often encountered by Jewish people in Russia.

He also explained that he hid the truth about my aunt’s whereabouts from us because the consequences of the truth leaking out to local authorities would have been dire. My mother and he could have lost their jobs, and my brothers and I would never be permitted to leave the borders of the country, which for (future) seamen would have been devastating. In fact, his sister who stayed behind was demoted due to my aunt’s departure for the United States; she was deemed guilty of betrayal by association.

Additional thoughts: My father unfortunately never got to read Soul in the Game. In the summer of 2017, he had a series of strokes which chipped away at his health, first rapidly and then very slowly. By the time I started working on the book, he was physically alive but mentally almost gone.

He passed away on August 10, 2023. Shortly after his death, I wrote an essay, “My Father – A Life Worth Living,” examining his life. It was the most difficult essay I have ever written. It was hard for many reasons. I was overrun by emotions – I had just lost a parent, my mentor, my best friend. I wanted to write something worthy of him; I wanted his life to be an example for others, including my kids.

In the process of trying to influence others by his example, I myself changed. Something snapped inside of me.

Losing a parent changes you – it brings your own mortality to the forefront. But it was more than that. While examining his life I inadvertently charted the life I wanted to lead. The inescapable feeling of pride and admiration I experienced made me want to be more like him.

One of my favorite expressions is from Confucius: “We all have two lives; the second one begins when we realize that we only have one.” Writing that essay was the beginning of my second life.

One more thing: Soul in the Game: The Art of a Meaningful Life is available in paper, digital, and audible formats. If you would like to receive a signed copy, donate to the following charities.

0 comments