I spent my youth in Murmansk, a city in the northwest part of Russia, located right above the Arctic Circle.

Murmansk owes its existence to its port. Thanks to the warming of the Gulf Stream, the port doesn’t freeze during the long winters, providing unique access to Russia from the north. During the Cold War, Murmansk’s coordinates must have been on the speed dial of the US military, as it is the headquarters of the Russian Northern Navy Fleet. Fans of Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October may remember Murmansk as the home base for the submarine Red October.

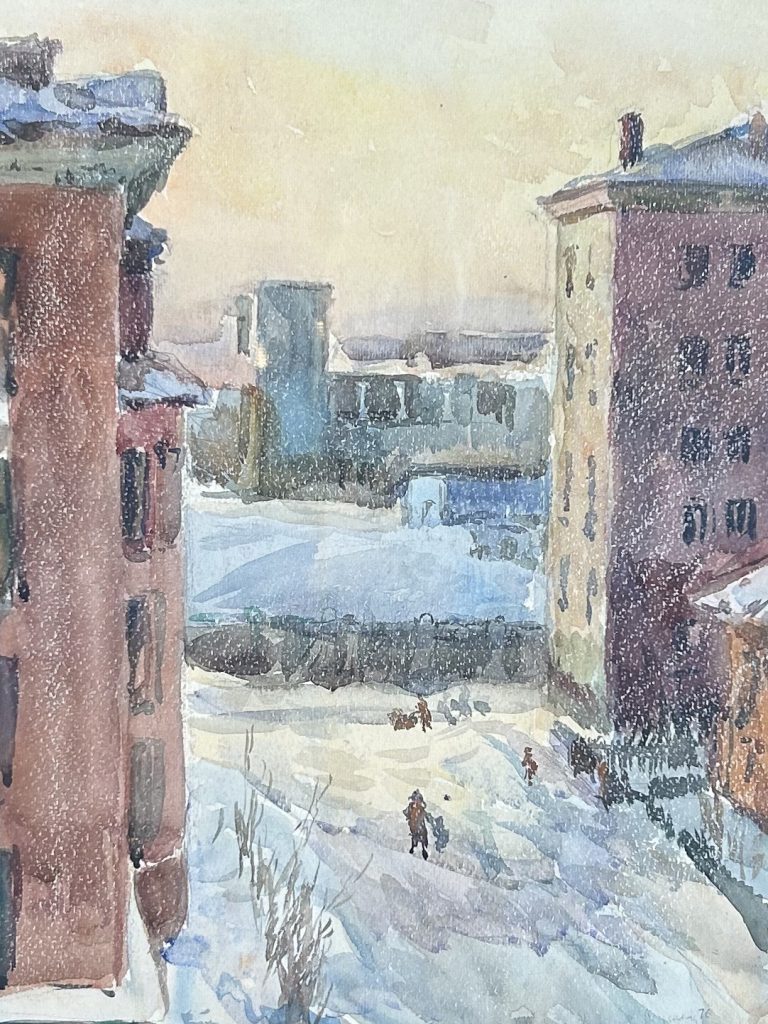

The winters are cold and dark; Murmansk makes Seattle look like a sunshine city. For six weeks every winter we lived without daylight. On those days during the winter when the sun would grace us with its presence, I still wouldn’t see it. In the morning I’d be walking to school in complete darkness. The sun would come out for 30 minutes around noon while I was in class. I’d walk home in complete darkness.

The city was so desperate for sun in the winter that it even created a day celebrating the sun, called Hello Sun. All this sounds awful, I know. Especially for my kids, who have spent their whole lives in Denver, with its 300 days of sunshine a year. But I was born into that life. I embraced it and never really thought twice about it.

Though I never felt it, I can see now how my parents’ life was very difficult. Murmansk is located so far north that the ground is permafrost – there is no vegetation to speak of. Most food had to be brought from other parts of the country. Murmansk had an abundance of fish (after all, it was a fishing port) and bread; that’s about it.

When I was a teenager, a few years before we left for the US, Russian bureaucrats figured out that if you grind fish, you can feed it to chickens. Suddenly we had an abundance of chickens. Unfortunately, the chickens that were fed fish tasted like fish. When I moved to the US, I could not eat chicken for ten years.

There was no fruit in stores during winter. In September, my parents would pickle cabbage in giant jars that we kept on our windowsills so it wouldn’t spoil. Pickled cabbage was one of our few sources of vitamins in winter. We’d also drink what was called “fish fat” (fish oil), an extract from cod liver that was our source of vitamins A and D.

Today when people look at me, at 5’10” (on a good hair day), standing next to my 19-year-old son Jonah, who is 6’3, they ask me why he’s so tall. I explain that I grew up in a place that had no sun or vegetation; and thus my diet, in addition to lacking vital vitamin D, lacked all other vitamins, too. Then I add that if I had grown up in Denver I would have been 6’5” and blond.

My mother always worried about what we were going to eat. Store shelves went through different phases of emptiness. Every month we were given vouchers that allowed us to buy a few pounds of meat per family member – if the store had meat. Even when they had meat it was for a short time and we had to stand in long lines to get it. My parents never complained. It was our life and the life of everyone around us. I did not know any other way.

But my parents had known a different, gentler life. My father grew up in Moscow. Being Jewish in the 1950s was difficult in Russia. There was hidden (not in-your-face) anti-Semitism. My father aced math in high school, even tutored other kids in the subject. Yet when he applied to university, he somehow “failed” the math test.

I don’t know whether, if he had applied to other universities, they would have accepted him, but the rebel in him decided to go study in a godforsaken place at a school that would accept him without even an entrance exam – Murmansk Marine Academy. They accepted anyone who was able to fog a mirror.

Late in the 1950s my father met my mother while visiting his relatives in Saratov, a beautiful 400-year-old Russian city on the Volga River. My mom was my father’s distant relative (not blood-related). They fell in love, and she moved to Murmansk.

My mom must have loved my dad very much to move from the comfort of an intellectual life in Saratov (she played piano and violin and went to the symphony on a regular basis with her parents) to the hellhole that Murmansk was at the time.

It was better in the 1960s than it had been in the 1950s, but it was still a fishermen’s town, where the only music you’d hear was the drunken sailors belting out bawdy seaman’s chants as they stumbled through the streets.

My parents could have left Murmansk for Moscow or Saratov. But all their friends were in Murmansk and my father had a great job there that he loved. He was a gifted and much-loved professor. My father had taught most of the high brass who occupied positions of power throughout Murmansk, and thus if we needed something my father knew someone who knew someone. That was Soviet Russia: Every single company or organization was owned by the government, and to get anything you had to know someone.

That included simple things like my brother wanting to transfer to a different school, or my parents wanting a larger apartment for their growing family to live in. As I write this, I realize how weird this sounds. Welcome to socialism.

This “power” my father had was born completely out of love and respect. My father liked walking home from the Academy, which was two miles (this is where I got my love for walking). This 30-minute walk always turned into a two-hour walk and talk journey, as my father would always meet people he knew and stop and have a ten-minute conversation with each. I think he enjoyed being loved and respected by others. He is a warm, honest, well-rounded, nonjudgmental human being, and a great listener. People love that. I remember the admiration with which people looked at my father.

If we moved from Murmansk, he would have had to give that all up. My mom could never ask him to do that. I only understand now, almost 40 years later, how much my mom loved my dad – she shielded him completely from the difficulties of the outside world. She just let him be him – he taught and painted. Worrying about what we were going to eat was my mother’s burden. Though this was a difficult life, we never starved. In fact, I didn’t know anyone who went hungry.

My mom gave up a career for our family. She had a graduate degree in physics from the university in Saratov, but in Murmansk she took just a part-time job working at an institute that studied the northern lights. Her work and her own interests were always secondary to taking care of the family. She put my father, my brothers, and me at the center of her life. In her late 40s, she found a sliver of daylight in her day and joined a choir. That is the only thing I remember my mother doing for herself.

These two watercolors by my father show the view from our apartment windows in Murmansk during winter. He painted them in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Both paintings are now hanging in the IMA HQ. They depict what Murmansk looked like in wintertime, with snow piled on the ground until late April.

Additional thoughts: As I reread the above, it sounds like my family had served a long prison sentence in Murmansk. Not at all. My parents taught me to find beauty in that life. Long winters were an excuse to play in the snow, tobogganing down the small hills Murmansk was full of. I am still nostalgic for walking during the dark polar nights on streets lit up by streetlights, feeling the freshness of cold air biting my cheeks, and hearing and feeling the crisp snow breaking under my feet.

On Sundays, my parents would take us skiing (what Americans call cross-country skiing). We would walk about a mile with our skis to the “sopki” (hills) and ski a few miles. I was lazy (still am), did not like carrying skis and poles for 30 minutes both ways, and never liked running (which is what cross-country skiing is, running on skis), but I loved spending time with my parents and my brothers.

Also, as a long-awaited reward for my “hard labor,” my father would always bring a thermos full of hot, sweet tea. It’s amazing how little I needed to be happy. Most importantly, I had unconditional, abundant parental love.

Love this, Vitaliy, thank you.