I’ll dedicate the next few musical notes to Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky. I have always had a difficult relationship with his music. My parents loved his first piano concerto, and I’ve listened to it a few thousand times over the years (I love it, too). At the same time, I was forced to listen to his music in school in Russia. Anytime I am forced into something I naturally start resenting it. This applies to Russian literature as well: my teachers turned Russian literature into Mark Twain’s definition of a “classic ”: a book that people praise and don’t read. I am still trying to get back into Russian literature, but Tchaikovsky’s incredible music has overcome my implanted childhood resentment to it, though it took time.

In the next few musical notes I’ll share Tchaikovsky’s music and what I’ve learned about him. There are several theories as to why Tchaikovsky died at age 53. The theory I heard when I was a child in Russia was that he died from cholera – probably from drinking contaminated water. However, there is another theory about his death: that he committed suicide. Tchaikovsky was a Russian national treasure, a symbol of Russian greatness, something the propaganda machine could point at and say, “Materialistic Americans have their poisonous hamburgers (and a chicken in every pot, and toilet paper, and…), but we got art.” This is also why the propaganda machine would censor a little-known fact about its national hero: Tchaikovsky was gay.

Today we see headlines about Putin’s homophobia, but as much as it’s convenient to blame it on Putin, it is not him but his country (admittedly, a very general statement). I did not learn of the existence of gay people until I was 17, and what I was told about them by my friends and the media was not much different from what the majority of Russians perceive today: that all gay people are AIDS-spreading pedophiles, so that being gay is a contagious. Also that one can become gay by observing gay behavior and that gays are responsible for the ongoing depopulation of Russia. (This is a new one and contains more than a kernel of self-denial: drinking unto death is the more likely explanation for Russian population shrinkage.) Russian homophobia goes back centuries and was in full flight in the late 19th century, the Tchaikovsky era.

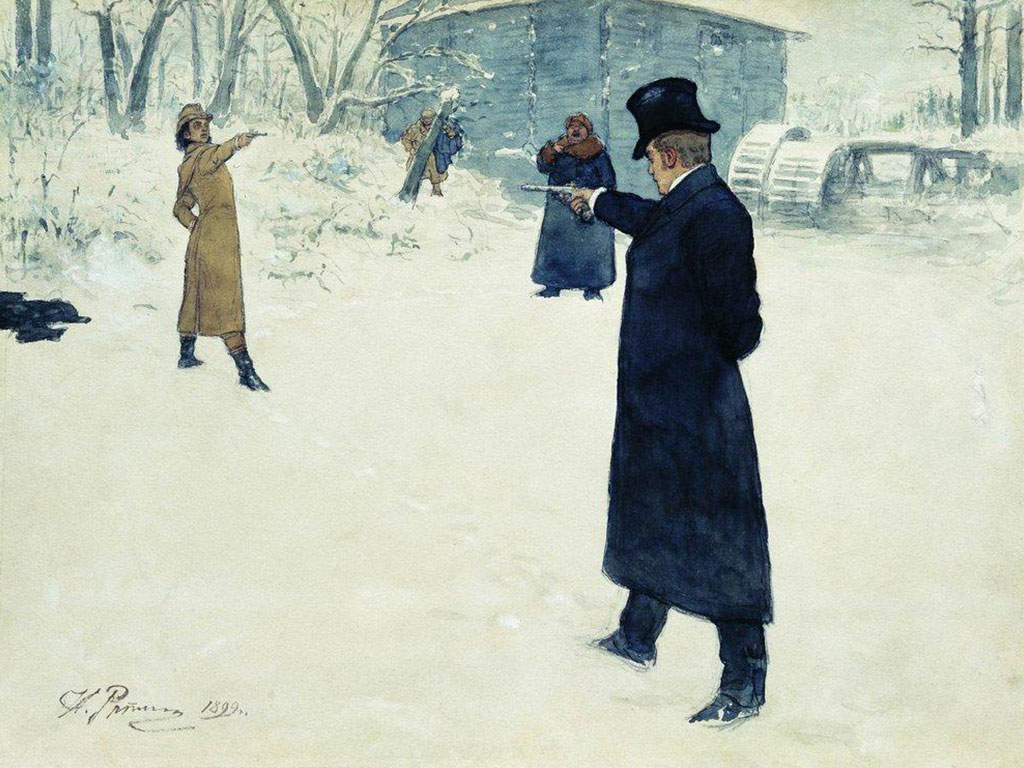

Tchaikovsky hid his gay “flaw” all his life. Many think the cholera story was a cover-up of his suicide. Tchaikovsky was caught out having an affair with Duke Stenbock-Thurmor’s nephew. The duke was going to write a letter of protest to the Czar. This would have supposedly brought disgrace to Tchaikovsky. A “court of honor” made up of his former classmates in St. Petersburg ordered Tchaikovsky to swallow poison. He did. Or so the story goes. We’ll never know which theory is true, the cholera or the suicide, but we do know that being in the closet all his life had an impact on his music. This will bring us, by and by, to Evgeniy Onegin (also known as Eugene Onegin).

Almost everything we know about Tchaikovsky today (and this is true about most classical composers) we learn through his letters exchanged with relatives and friends. In one letter to his brother when he was in his twenties, he says that he needs to get married. Not because he wants to have a family, but to help maintain his cover story. “I’ll marry anyone that will have me.” Shortly after, he got a fan letter from one of his former students at conservatory. She confessed her love for him. Tchaikovsky did not remember her, but they met. This is where the story gets murky. She wanted to marry him. He tried to explain to her that he was not interested in women and that it would be a fake marriage. Either he did not communicate that part that well or she did not understand it. They got married. She wanted more from him that he could give her. He could not physically stand her. His brother made up a story that doctors had told Tchaikovsky that his wife was making him sick. They separated.

At about the same time Tchaikovsky received a letter from Nedezhda von Meck, a very wealthy widow of a railroad magnate, who was also a fan of his music. Von Meck wanted to be his pen pal. She also ended up being his sugar mama (she supported him for thirteen years). They became close friends and exchanged over 1,000 letters. He dedicated his Symphony Number 4 to her. (I’ve written about that symphony here). But they never actually met!

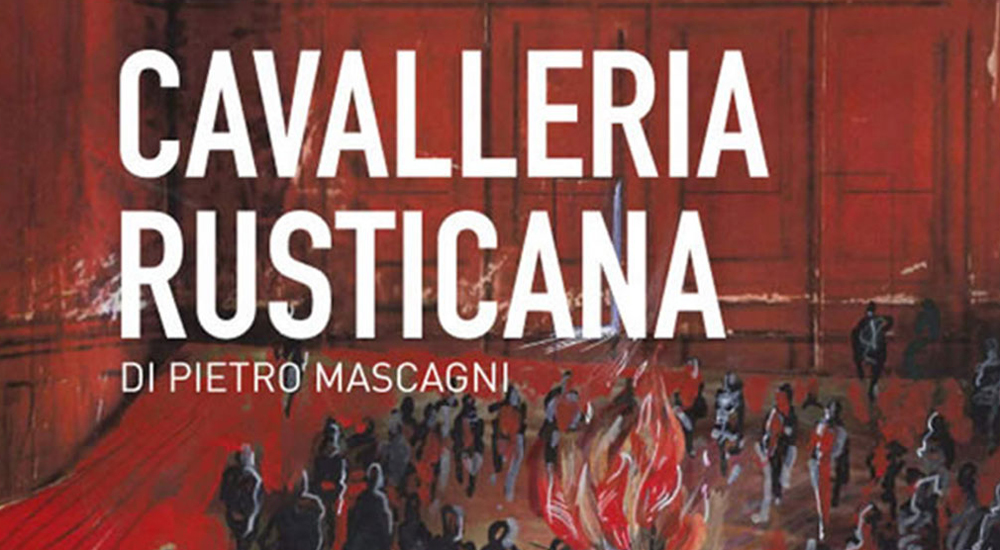

There is a reason why I am writing about this. At about the time when Tchaikovsky received letters from his future wife and Nedezhda von Meck, he read Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. (For those who did not go in for the Russian classics, Pushkin is the godfather of Russian literature, the Russian Shakespeare, if you will.) Anyway, Tchaikovsky was asked many times to compose an opera based on Eugene Onegin. He always declined, because he felt the bar raised by Pushkin was too high. But one sleepless night he read Eugene Onegin and became infatuated with the “letter scene” (see how this all starts to make sense?). Tatyana, who is love with Onegin, is writing him a letter, confessing her love for him. It is a deeply emotional scene, and this is the scene that pushed Tchaikovsky into writing the opera. Her felt a significant personal connection to it.

We saw Eugene Onegin in “Live in HD” broadcast from the Met last month. To my great surprise, my son loved this opera (in some cultures, taking a twelve-year-old to see opera would be considered child abuse). So today I want to share with you a few excerpts from this opera:

Letter Scene by Anna Netrebko (the performance we saw). Here is another version of that scene by Kristine Opolais (notice the completely different stage set)

Lensky’s Aria by Rolando Vilazon (one of my favorite performances)

Prince Gremlin’s Aria (Alexei’s Tanovski sang it in the performance we saw at the Met)

I’ll dedicate the next few musical notes to Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky. I have always had a difficult relationship with his music. My parents loved his first piano concerto, and I’ve listened to it a few thousand times over the years (I love it, too). At the same time, I was forced to listen to his music in school in Russia. Anytime I am forced into something I naturally start resenting it. This applies to Russian literature as well: my teachers turned Russian literature into Mark Twain’s definition of a “classic ”: a book that people praise and don’t read. I am still trying to get back into Russian literature, but Tchaikovsky’s incredible music has overcome my implanted childhood resentment to it, though it took time.

In the next few musical notes I’ll share Tchaikovsky’s music and what I’ve learned about him. There are several theories as to why Tchaikovsky died at age 53. The theory I heard when I was a child in Russia was that he died from cholera – probably from drinking contaminated water. However, there is another theory about his death: that he committed suicide. Tchaikovsky was a Russian national treasure, a symbol of Russian greatness, something the propaganda machine could point at and say, “Materialistic Americans have their poisonous hamburgers (and a chicken in every pot, and toilet paper, and…), but we got art.” This is also why the propaganda machine would censor a little-known fact about its national hero: Tchaikovsky was gay.

Today we see headlines about Putin’s homophobia, but as much as it’s convenient to blame it on Putin, it is not him but his country (admittedly, a very general statement). I did not learn of the existence of gay people until I was 17, and what I was told about them by my friends and the media was not much different from what the majority of Russians perceive today: that all gay people are AIDS-spreading pedophiles, so that being gay is a contagious. Also that one can become gay by observing gay behavior and that gays are responsible for the ongoing depopulation of Russia. (This is a new one and contains more than a kernel of self-denial: drinking unto death is the more likely explanation for Russian population shrinkage.) Russian homophobia goes back centuries and was in full flight in the late 19th century, the Tchaikovsky era.

Tchaikovsky hid his gay “flaw” all his life. Many think the cholera story was a cover-up of his suicide. Tchaikovsky was caught out having an affair with Duke Stenbock-Thurmor’s nephew. The duke was going to write a letter of protest to the Czar. This would have supposedly brought disgrace to Tchaikovsky. A “court of honor” made up of his former classmates in St. Petersburg ordered Tchaikovsky to swallow poison. He did. Or so the story goes. We’ll never know which theory is true, the cholera or the suicide, but we do know that being in the closet all his life had an impact on his music. This will bring us, by and by, to Evgeniy Onegin (also known as Eugene Onegin).

Almost everything we know about Tchaikovsky today (and this is true about most classical composers) we learn through his letters exchanged with relatives and friends. In one letter to his brother when he was in his twenties, he says that he needs to get married. Not because he wants to have a family, but to help maintain his cover story. “I’ll marry anyone that will have me.” Shortly after, he got a fan letter from one of his former students at conservatory. She confessed her love for him. Tchaikovsky did not remember her, but they met. This is where the story gets murky. She wanted to marry him. He tried to explain to her that he was not interested in women and that it would be a fake marriage. Either he did not communicate that part that well or she did not understand it. They got married. She wanted more from him that he could give her. He could not physically stand her. His brother made up a story that doctors had told Tchaikovsky that his wife was making him sick. They separated.

At about the same time Tchaikovsky received a letter from Nedezhda von Meck, a very wealthy widow of a railroad magnate, who was also a fan of his music. Von Meck wanted to be his pen pal. She also ended up being his sugar mama (she supported him for thirteen years). They became close friends and exchanged over 1,000 letters. He dedicated his Symphony Number 4 to her. (I’ve written about that symphony here). But they never actually met!

There is a reason why I am writing about this. At about the time when Tchaikovsky received letters from his future wife and Nedezhda von Meck, he read Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin. (For those who did not go in for the Russian classics, Pushkin is the godfather of Russian literature, the Russian Shakespeare, if you will.) Anyway, Tchaikovsky was asked many times to compose an opera based on Eugene Onegin. He always declined, because he felt the bar raised by Pushkin was too high. But one sleepless night he read Eugene Onegin and became infatuated with the “letter scene” (see how this all starts to make sense?). Tatyana, who is love with Onegin, is writing him a letter, confessing her love for him. It is a deeply emotional scene, and this is the scene that pushed Tchaikovsky into writing the opera. Her felt a significant personal connection to it.

We saw Eugene Onegin in “Live in HD” broadcast from the Met last month. To my great surprise, my son loved this opera (in some cultures, taking a twelve-year-old to see opera would be considered child abuse). So today I want to share with you a few excerpts from this opera:

Letter Scene by Anna Netrebko (the performance we saw). Here is another version of that scene by Kristine Opolais (notice the completely different stage set)

Lensky’s Aria by Rolando Vilazon (one of my favorite performances)

Prince Gremlin’s Aria (Alexei’s Tanovski sang it in the performance we saw at the Met)

0 comments