I originally wrote this piece in 2016, but it’s just as relevant today.

“This is a very bad, incoherent piece.” I received this feedback from a reader concerning an article I had recently written. I don’t expect everyone to agree with me, and I welcome negative feedback because it provides an opportunity to learn. But this stung. If this comment had been about almost any other article I’ve written this year, I’d probably have filed it under “let’s agree to disagree.” Looking back, however, I’m not sure this reader was wrong. While I stand by my original thesis, I think I could have made my case more clearly. So here is what I meant to say:

We are in the freakiest investment environment ever. Investors are buying bonds because they are looking for capital appreciation — essentially gambling that the price of an asset delivering negative (if you are in certain parts of Europe or Japan) or almost no (if you are in the U.S.) current income will go up. And investors are buying stocks solely for income. Dear reader, this is an upside-down world.

In my original article I addressed a group of stocks I call bond substitutes: stocks bought solely for their dividend yield. They are a special group of companies that have been around forever and that are usually perceived to be high-quality companies — think Coca-Cola, Kimberly-Clark Corp. and Campbell Soup Co., among others. I picked on Coke just because it is one of the most quintessentially American companies. I figured I’d just use Coke as an example to make a much broader point about the dangers of focusing solely on yield.

Equity returns come from two sources: stock appreciation and dividends. Stock appreciation is mathematically driven by two variables: earnings growth and change in the price-to-earnings ratio. In other words, take any stock in your portfolio, go back five years, and you can deconstruct the return you received from it by looking at the sum of three variables: earnings growth, P/E change and dividends.

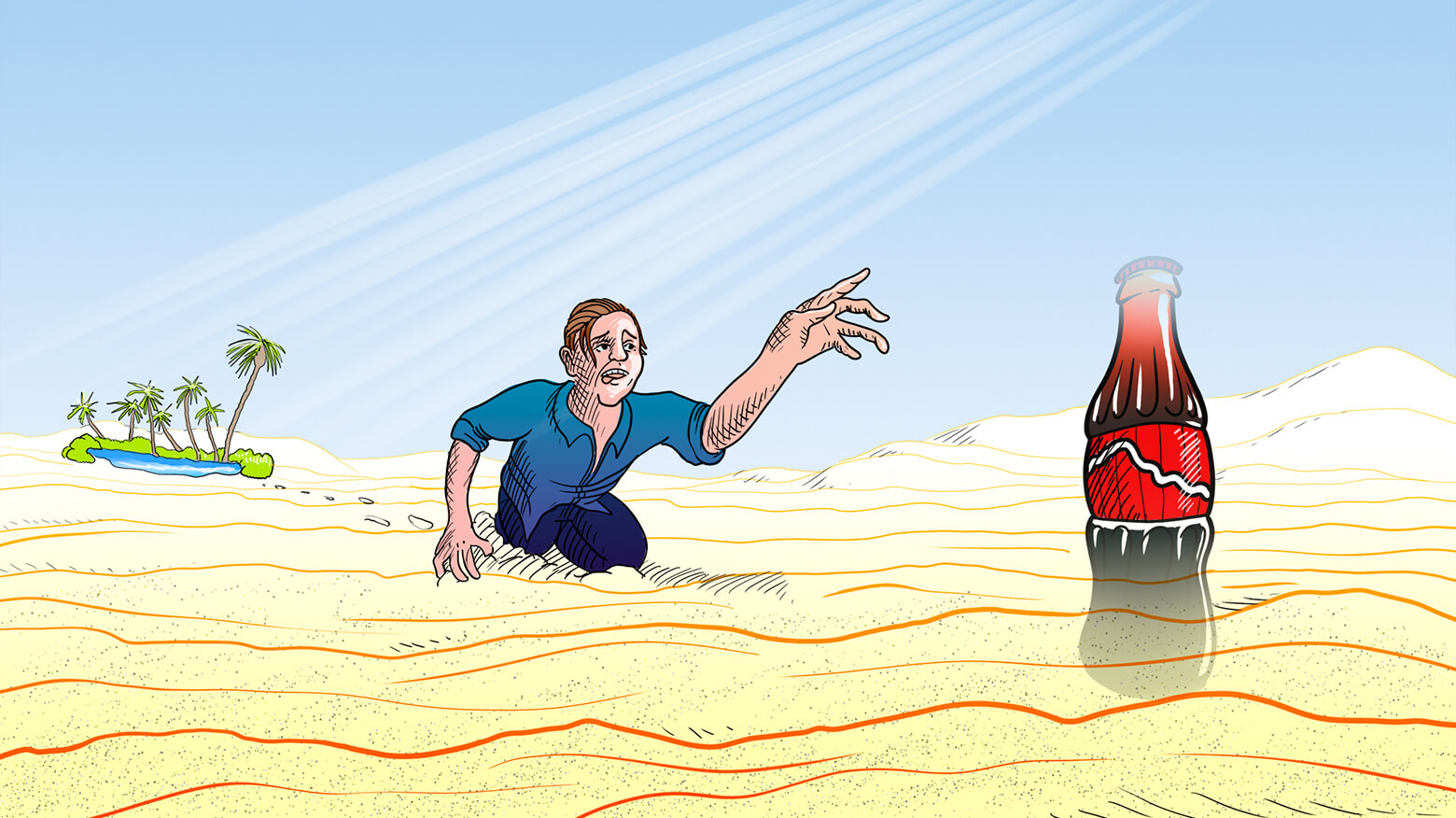

Today investors look at Coke, admire the return it has delivered over the last five years, mull over its 3 percent dividend, and say to themselves, “Three percent is better than the 1.7 percent I get from Treasuries.” When they do this, however, they focus on one shiny object (the dividend yield) but ignore the other parts of the aforementioned stock market math formula that are less shiny (earnings growth and P/E) and are barely positive in this example and will likely turn negative.

Coke is a mature company that already has conquered the world — unless it goes to Mars with Elon Musk , it is done on this planet. And it has a lot of consumption trends going against it. Consumption of its fizzy drink in developed markets is on the decline; each can of Coke packs a full dose of your recommended daily consumption of sugar (sorry, Warren Buffett). And diet drinks simply scare consumers, as they are not quite sure what kind of Frankenstein process Coke had to go through to remove the sugar and calories and turn the drink into whatever it is. Coke’s earnings may very well grow. But you can make a reasonable argument that they will actually shrink over the next five to ten years. Growth in Coke’s earnings is not guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution, no matter how American this company is.

Coke’s valuation is very rich. Can this number go much higher? Sure, why not? As Keynes famously said, “The market can stay irrational longer than you can remain solvent” (or sane). But let’s be clear: buying at those valuations is not investing, it’s gambling. Do it and you’re not much different from a fellow who goes to Las Vegas, prays and puts his chips on red. You are betting that the music will continue to play and interest rates will remain where they are, or that investors will continue to pay a lot for a little.

If Coke continues to pay its dividend, which is probably a very safe bet, but its earnings don’t grow, and its P/E ratio declines to 15 (which at that point will be a generous number), then it would get cut roughly in half.

I suggest you think of this as a public service announcement: If you own stocks solely for their dividends, you are ignoring the other parts of the stock market equation that, though they are less shiny (and less tangible) than dividends, are just as important to your future returns.

0 comments