Though first written in 2018, this article remains relevant to this day.

We always look at our investment process and ask ourselves, “What can we do better?” How can we increase returns and lower risk?

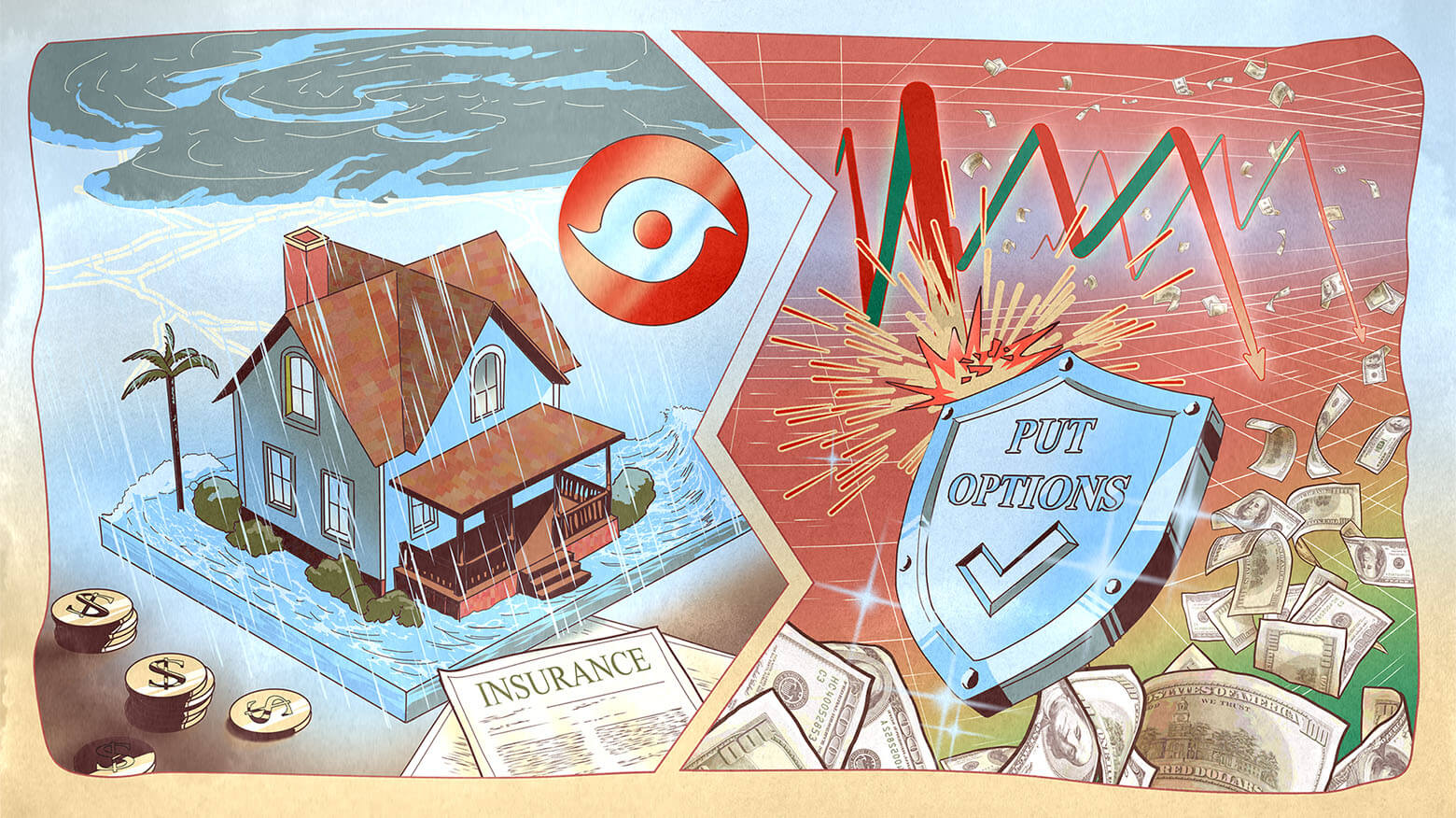

One way: We can hedge a portion of our market exposure with put options. Put options are contracts that trade on an exchange which give the buyer (us) a right, not an obligation, to sell stock (or Index, ETF, or other security) at a specific price for a certain period of time. Put options are cash settled, so when we exercise it or it expires we get cash in lieu of its value. Buying put options is very similar to buying hurricane insurance. We pay a premium, and that is the only cost we bear. Let’s restate this: The only risk we take is that the hurricane doesn’t hit or, in our case, that the stock market doesn’t decline, in which case our premium was “wasted.”

When you buy hurricane insurance you don’t suddenly start wishing for a hurricane, but you do get peace of mind from knowing that if Richard or Betty (we name hurricanes like we name pets) pays you a visit, the insurance company will restore your house to its original state.

We look at options “insurance” the same way we look at any asset: It can make sense at one price but make no sense at another. As you will see, at today’s price they make a lot of sense.

For the sake of simplicity let’s make a few assumptions: First, your portfolio is 100% correlated to the stock market. Second, your portfolio is 100% invested. And finally, let’s assume we’d be buying put options to insure your whole portfolio. These assumptions will simplify our example – we’ll modify them later.

Based on our assumptions, we’d buy put options on ETFs that track a particular stock market index – let’s say the S&P 500. In January 2018, for example, if we bought options on the S&P 500 ETF, SPY, that expire in one year and that were 5% out of the money (they wouldn’t start paying us until the S&P declines 5% or more from that point – think of this 5% as our deductible), the cost of insuring the entire portfolio would have been about 4% of its total value. For a $1 million portfolio it would be $40,000.

If the stock market decline is greater than 5%, the insurance kicks in. After a 5% decline the value of our stock options starts going up proportionally to the decline in the portfolio. If the stock market falls 20%, the $1 million portfolio declines to $800,000, but this $200,000 loss is offset by the appreciation of our put options, which go up by roughly $150,000. Thus the value of the portfolio is now $950,000 (remember our 5% deductible). Actually that number will most likely be less – somewhere between $910,000 and $950,000, because we paid $40,000 for the put options.

Without getting too deep into the weeds, the price of an option is driven by two additional factors: time (options are not good wine; they get cheaper with age) and expected volatility, which we’ll discuss next.

Let’s say you are insuring a home somewhere on the Florida coast. The general formula to calculate the cost of insurance is probability of loss times severity of loss. According to a study by Colorado State University, the climatological probability that the coast of Florida will get hit by a major hurricane in any particular year is 21%, so once every five years or so.

A 21% probability doesn’t mean that a hurricane will pay a visit every fifth year; no, it actually means that over a 100-year period there will on average be 20 hurricanes hitting the Florida coast. Hurricanes may, however, decide to pay a visit two or three years in a row and then take eight or ten years off.

21% is the number an insurance company uses to figure out the intrinsic cost of the insurance. But this is where we have to draw a distinction between climatological probability of loss (intrinsic or true cost) and expected probability of loss.

There are other factors that go into the total cost of the insurance contract, including the size of the policy, its duration, and the deductible. But if you hold all these factors constant, the only number that fluctuates due to supply and demand in the insurance market is the expected probability of loss.

A year after a hurricane, homeowners are still licking their wounds from last year’s Richard or Betty. The pain is so recent that those who were hit expect that hurricanes will happen a lot more often and thus the expected probability (in the eyes of these consumers) rises to … pick a number; let’s say 50% (a hurricane every two years). (The insurance industry may have had its capital depleted by recent hurricanes, which will also drive prices higher, but we’ll ignore this factor in our discussion.)

However, if there is no hurricane for a while, let’s say for eight years, the memory and the pain of the last hurricane fade away. A new wave of homeowners moves in, who have seen hurricanes only from the comfort of their leather couches on the Weather Channel. Now the expectation of another hurricane drops to, let’s say, 10% (a storm every ten years).

Thus, though expected probability and thus insurance cost has fluctuated dramatically from 50% to 10%, intrinsic value has not changed; it is still 21%. This example is extremely oversimplified, but the key point is still the same: A rational homeowner would want to buy insurance when no one expected a hurricane to visit Florida and lock in that price for as long as possible. If you are an insurance company you want to write as much insurance as you can when hurricanes are priced at 50% expected probability, and you want to be out of the market when they are priced at a 10% probability.

In the options market, expected probability of loss is expressed in terms of the volatility that is priced into options. A long bull market (despite some small interruptions) has eroded even the most unpleasant memories of the 2008 decline. Fear has been replaced by euphoria that has been further amplified by the steady daily appreciation of stocks. The mindset that markets will never decline ever again has gradually seeped into the collective stock market psyche. This is why volatility is cheap! How cheap? Average volatility priced into options since 2004 was about 18%; today it is at 10%. In 2008 it reached 80%, and it has reached 40% a few times since 2008.

Volatility is quickly becoming one of the most interesting assets in the otherwise not very interesting stock market. But the situation in the stock market is even more interesting than in the hurricane insurance market.

Stock markets are fueled by two often contradictory forces: human emotions and movement towards fair value. Human emotions may divorce stocks from their fair value for a considerable period of time, but movement towards fair value can only be postponed but not suspended. During bull markets greed begets greed and stock market valuations go from cheap to average to high to super-high to extra-super-high – we are running out of superlatives, but we hope you get the point: Valuations march ever higher … until the music stops.

It is hard to know what will trigger the “stops” part, but in the late stage of the bull market, stock market behavior is driven less and less by fundamental factors and more and more resembles a Ponzi scheme (though market commentators come up with plenty of rational explanations to wrap around their “this time is different” narrative).

Stocks march higher until the market runs out of buyers and collapses under its own weight. This is how movement towards fair value takes place – except that, historically, markets have rarely stopped at fair value; they have fallen to levels well below fair value.

We’ll address the market’s current (over)valuation further on in this letter.

We are not meteorologists, but we believe there is an important difference between hurricanes and stocks. Just as when you flip a coin each flip is an independent event and completely unconnected to the previous flip, hurricanes are independent events – just because Richard paid a visit to Florida last year does not change the probability of Betty’s appearance next year. Betty is not aware of Richard’s past misdeeds.

In contrast, the probability of a significant market decline is not constant; it is dependent on past movements of stocks. As markets stretch higher and higher, bulk of the appreciation was driven by expansion of price to earnings. Market valuation which was already high went higher. The gap between the price and intrinsic value creates a rubber band-like tension. The wider the gap the greater the tension and risk of eventually embarking on the return trip towards fair value.

Thus, in the case of the hurricane the climatological probability of 21% of loss remains constant no matter whether Richard or Betty appears, but in the stock market the probability of a sharp decline (an equities hurricane) increases as the gap between price and fair value widens.

In other words, today the value of volatility has increased while its price is making new lows. This is why we believe volatility is one of the most interesting assets we see now.

We are not market timers. We have no idea what the stock market will do today or tomorrow, but we look at buying put options as an opportunity to hedge our portfolios with what we believe is significantly undervalued insurance.

Let’s delve into the practicality of our hedging strategy and modify some assumptions we made in the oversimplified example above. First, our portfolios are not 100% correlated to market indices. Considering that we own high-quality companies that are significantly undervalued, we believe our stocks will (temporarily) decline less than the market if there is a significant correction. Second, we have a lot of cash, which doesn’t require hedging.

Let’s say your account is 60% invested. We only need to worry about hedging that 60%. And considering that our stocks will decline less than the market, we need to buy puts to protect less than 60%. How much less? Historically our stocks have declined a lot less than the market during significant sell-offs. Our average portfolio was down 17-18% in 2008 when markets were down 35-45%. Our guestimate, therefore, is that we need to hedge about half of 60% or 30% of the total portfolio. So the total cost of insuring the portfolio against a decline of 5% or greater for a year would be 1.2% (4% – the cost of “insuring” the total portfolio – times 30%).

You can see how this strategy can reduce risk, but can it increase returns? The answer is a bit more complex and has two parts: First, if the market takes a deep dive, our appreciated put options together with cash will have increased buying power, since everything around us will be cheaper. And second, depending on when it happens – how much time value is left in the option – the value of the option may jump dramatically, as the market will be pricing in not 10% volatility but a much higher number – 30%, 40%? – your guess is as good as ours.

IMA’s ultimate goal is to produce good risk-adjusted returns while keeping volatility of our clients’ blood pressure level to a minimum. We try to achieve this through our conservative stock selection, our transparent (sometimes overly long) communication, and now through buying inexpensive insurance on the portion of your portfolio.

Our view on what true risk is has not changed. To value investors, true risk is not volatility (a stock temporarily declining in price), but a permanent loss of capital (the stock price decline is permanent). Our hedging strategy goal is to take advantage of an undervalued asset – volatility – and to decrease your (future) blood pressure just a little.

0 comments