Markets are efficient, or so we’ve been told. I am not here to put a rebuttal to this academic nonsense, but let me give you one of the core reasons why markets are and will remain inefficient: because human beings are efficient.

To function in everyday life, our brains are used to simplifying complex problems, through pattern recognition. We become accustomed to drawing straight lines when we see two points, and if we get a third or fourth point that fits the line, our confidence about the longevity (continuity) of the line increases exponentially. We become excited, even certain, about prospects of the company we’ve invested in when its stock has gone up for a long period of time, while we often dismiss stocks that have declined or flat-lined, especially if that happened for a considerable period of time.

Imagine an analyst bringing a “fresh” stock idea to a portfolio manager at a large mutual fund. He’d say something among these lines: Cisco is a buy, it has a bulletproof balance sheet with $25 billion of net cash (cash less debt), the stock is cheap – trading at 9 times earnings (excluding net cash), it’s providing double-digit returns on capital, and it is a dominant player in the industry, which is poised to grow at a faster rate than the economy, since, thanks to iPads, Androids, Kindles, Hulus, and Netflixes, we’ll all continue to consume digital content.

I can just see the portfolio manager’s smile, his laugh and comment that “This stock is a value trap, it has gone nowhere in more than a decade.” I’m glad I’m not that analyst, as I’d have a huge burden to overcome. After all, Cisco has shattered the dotcom dreams of many investors in the years following 1999, when it hit $80 a share and, for a brief moment, was one of the most valuable companies in the world, sporting a modest P/E of 100+. Since then, gravity has caught up with Cisco’s stock (it always does), and it has declined almost 80% from its highs, to $17. Most investors who bought the stock since ’99 either lost or made no money. Draw a straight line through its chart (you have more than a decade’s worth of data points), and you see it’s either going to zero or at least will continue to go nowhere. Now, you add to this performance a few quarters of disappointing Wall Street guidance, and you have an untouchable, un-recommendable stock.

However, fundamentals – take any metric: revenues, earnings, cash flows – will tell a very different story: they either tripled or quadrupled since 1999. Through no fault of its own, Cisco’s stock was too expensive in 1999, and it took time for the stock to catch up to its fundamentals. Of course, as usually happens, investors get overexcited on both sides of valuation. The same investors who could not get enough of Cisco at over 100 times a little more than decade ago, don’t want touch it at 9 times earnings with a ten-foot pole. (Here is efficient market for you). The dark shadow of the stock performance hides an attractive investment.

Cisco is not a spring chicken anymore, it has over $40 billion in sales. It will likely see some margin compression as parts of its business mature. Its revenue and earnings will grow at a slower rate than they did over the last decade. But at its current price Cisco doesn’t have to do anything heroic to justify its valuation, it just needs to show that it has a pulse.

It is very difficult to get a unique insight into Cisco’s business or that of any large-cap stock; after all, they are followed by a small army of analysts (Cisco is followed by some 40 analysts). Some sell-side analysts undoubtedly know what John Chambers’ (Cisco’s CEO) favorite cereal is, and can recite the model number of every Cisco router by heart. Most of us cannot compete with that, nor do we need to.

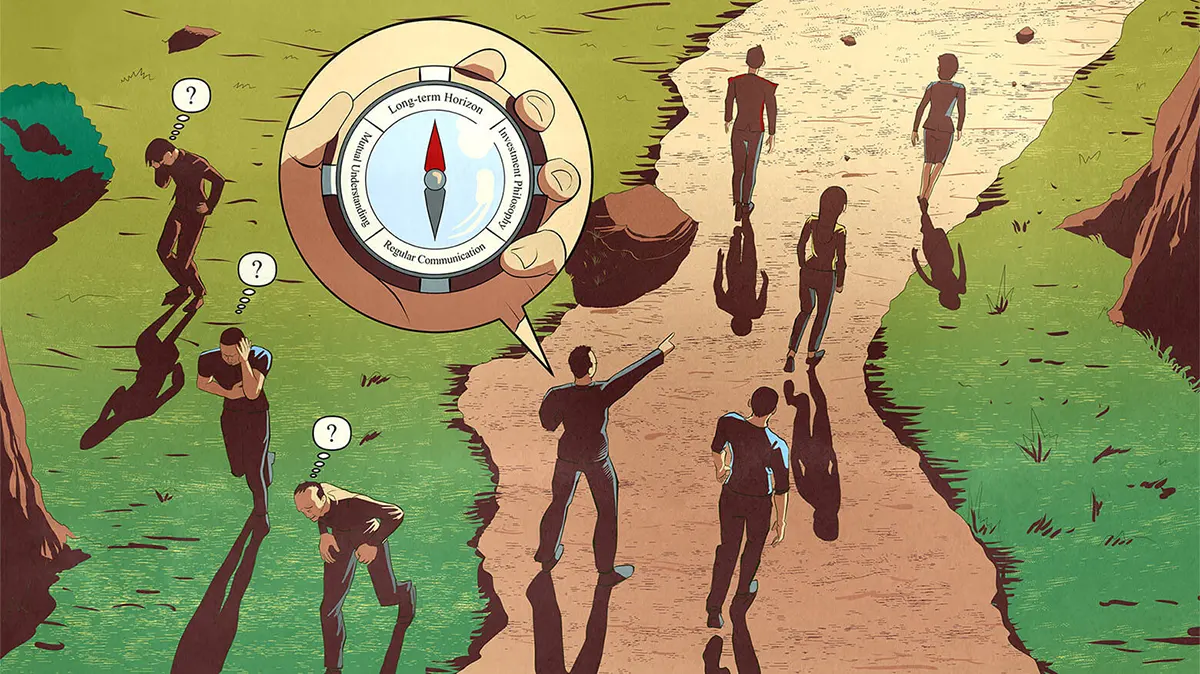

First of all, you need to have a time horizon longer than Wall Street’s. Wall Street is very short-term-oriented, and mutual fund managers are judged and compensated on their monthly and quarterly performance. Sell-side analysts are there to serve their buy-side masters, and thus expend their energy analyzing the next quarter, not the next five years. Therefore a time horizon longer than Wall Street is significant competitive advantage in itself. Cisco’s earnings three, five years from now are likely to be significantly higher than they are today.

It is also important to understand that even a much-followed stock like Cisco will suffer from inefficiency (which as a value investor I welcome), due to investors confusing the lousy stock with the company’s fundamental performance. That is how you find high-quality companies at bargain-basement prices.

Understanding what happened in the past is important, not because it is the precursor to the future, but because it helps to build the analytical bridge, through our own analysis, from today into the future. Be inefficient – don’t draw straight lines.

This article was published in Institutional Investor Magazine.

P.S. Watercolor “Paris Flower Market” by my father Naum Katsenelson

0 comments