Over the past decade, the Federal Reserve has manipulated asset prices by interfering with free markets by deciding what both short-term and long-term interest rates should be. This resulted in an increase in risk-taking behavior among investors. Risk became a four-letter word uttered only by curmudgeons; the only thing investors feared was being left out. The more risk you took, the more money you made – until you lost it all.

The First Law of Thermodynamics states that energy cannot be created or destroyed, but can be converted from one form to another. This principle applies to financial markets as well, where risk does not dissipate but, like a hot potato, gets transferred through time from one party to another.

We are observing this today in our economy. For every issuer and seller of long-term bonds that yielded next to nothing, there was a buyer who is losing money today as interest rates have risen suddenly and the prices of bonds dropped.

Over the past decade, consumers refinanced their houses with 2.5% mortgages. Some of these loans were kept by banks, while others were converted into mortgage-backed securities and sold to insurance companies, pension funds, corporations, and consumers. The majority of mortgages are fixed-rate, so consumers’ ability to remain in their homes is not affected by rising interest rates. However, the risk did not leave the system; it just got transferred from consumers to banks.

Today, long-term mortgages, these seemingly low-risk instruments, have declined in value by 20-30%. Not only mortgages have suffered these declines, trillions in long-term bonds issued by government and corporations at near-zero interest rates are burning holes in the pockets of those who bought them.

The human mind is conditioned to fight the last war. We usually compare inklings of new crises to past ones. Mark Twain famously said, “History does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” The scars and pain from past mistakes have been seared into us and changed our behavior, at least while the memory of past pain remains with society. This is why past wars and past crises rarely repeat verbatim; they merely rhyme in slightly different ways.

The Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 is still fresh in our society’s memory, so the US financial system is in better shape today, at least to avoid or survive through a crisis of the same type and magnitude. That’s what we thought. The US banking system now has higher reserves and more conservative underwriting standards. No more “liar” loans or “ninja” loans.

But.

Thanks to Uncle Sam spraying 5 trillion dollars from helicopters during the pandemic, all banks were flooded with consumer deposits that either paid no interest (non-interest-bearing) or almost no interest (interest-bearing). Banks had a dilemma: They had all this free money (deposits) that did nothing for profits if it sat idle. So, they loaned or invested the money, and they had learned their lesson from the GFC and did not take on higher credit risk; but they took a different risk – duration risk. And why not – for the last three decades interest rates had gone only one way – down.

Also, this is what banks do – they borrow short-term (deposits) and lend long-term. However, because rates were so low, many banks had to go very long-term to capture extra yield. This worked for a long time, and banks were minting money. But then inflation spiked, rates went vertical, and losses skyrocketed – long-term bonds declined 20-40% in months.

Banks were hurt twice, on both the asset and liability sides of the balance sheet. If they chose to categorize long-term bonds as available for sale, they had to mark them to market and immediately book losses, reducing their equity, which capped their ability to lend without shrinking their cushion to withstand future losses.

But if they categorized long-term bonds in the hold-to-maturity section of the balance sheet, they didn’t have to realize the losses, but the nightmare would reappear for a decade or longer on their income statements.

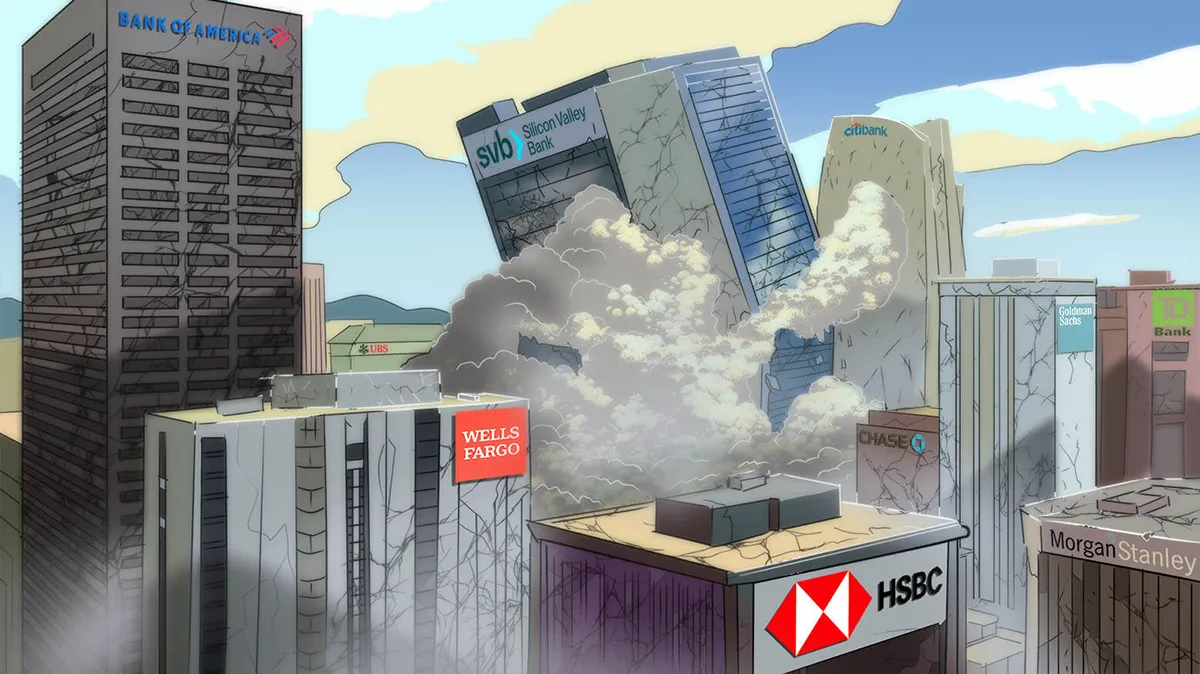

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) may be an extreme example, but it gave us a preview at a 100x magnification of what many banks are facing today. SVB is also a sad demonstration of how volatile deposits are. SVB was awash with deposits from its customers, mainly startups, raising money in the venture capital boom. It invested a large portion of these deposits into mortgages and US Treasuries that paid around 2.5%. Then the boom ended, and startups, which are usually in a perpetual state of losing money, started to deplete their cash balances. As they withdrew their deposits, SVB had to sell its underwater bond portfolio and realize about a 10% loss. With every dollar of deposits withdrawn, it had to transfer 10 cents from the equity (shareholder) side of the balance sheet. SVB was running out of those 10 cents.

SVB was going to raise equity (issue stock) to fill in the hole caused by the decline in bonds, but depositors ran for the door, forcing further liquidations of underwater securities. SVB ran out of equity, which put the company into bankruptcy.

SVB went through an almost a classic run on the bank (we’ll come back to that later, in part 2).

Even if SVB had managed to issue equity, substantially diluting its shareholders, it would have had to find a new way to finance its long-term loan portfolio, while interest rates had gone up a lot – borrowing at 4% and being paid 2.5% is not a sustainable business model.

A similar scenario awaits the rest of our banking system, which is drowning in consumer deposits today, if interest rates and prices stay at this level or go higher. American consumers will do what they are unmatched at: withdraw and spend the savings that were given to them by their kind Uncle Sam. Thus deposits (both interest and non-interest-bearing), the banks’ cheapest cost of funding, will be leaving banks to pay for the rising costs of tomatoes and avocados at Kroger and shoes at Macy’s.

Also, while interest rates were near zero, consumers did not care if their deposits paid interest or not, as the interest amounted to almost nothing. However, as inflation has spiked and interest rates have jumped, leaving money in a checking account that pays nothing has become very costly. As consumers shift more money to interest-bearing deposits, then, just like SVB, more banks will be forced to borrow at 4% (instead of 0%) to be paid 2.5% for 30-year mortgages that are in the hold-till-maturity column of their balance sheets.

God forbid inflation rages on (less likely now; more on that next) and short-term rates rise higher, or those 2.5% mortgages will be financed at 7-8% deposits and other sources of funding.

This has a significant implication for the economy. What we are likely going to experience is the opposite of what we observed over last 10 years: Credit will become dear and financial institutions will not be stretching for yield. Losses from the declines in long-dated assets are going to reduce banks’ equity and their earnings power. From the perspective of the economy as a whole, this also reduces banks’ ability to lend, sucking credit out of the economy. The cost of financing of everything from cars to factories will rise.

The decline in banks’ equity also weakens the banking system’s ability to handle the higher defaults that will inevitably come in the next recession.

The above may prove to be wrong if inflation turns to deflation, the Fed stops tightening and resumes its normal behavior of helicoptering money, and long-term interest rates decline, taking bond prices higher.

Key takeaways

- The Silicon Valley Bank collapse serves as a 100x magnification preview of the challenges many banks are facing due to the rapid rise in interest rates and the resulting devaluation of long-term bonds.

- SVB’s situation exemplifies how risk doesn’t disappear but gets transferred through the financial system, as per the First Law of Thermodynamics applied to finance.

- The Silicon Valley Bank collapse highlights the volatility of deposits, especially those tied to boom-and-bust cycles like the venture capital industry.

- SVB’s predicament of having to sell underwater bonds to meet deposit withdrawals, leading to equity depletion, is a scenario that could play out more widely in the banking system.

- The Silicon Valley Bank collapse underscores the broader challenge for banks: financing long-term, low-interest assets with increasingly expensive short-term liabilities, potentially leading to reduced lending capacity and economic implications.

Foo, Vitaly, this is not a classic libertarian solution:

“Banks are utilities and should be regulated as such by the government.”

I think free markets are much more capable of “regulating” the behavior of bankers than is the Fed, the SEC, or the FDIC. What startup with $100,000,000+ in cash would put its money into a financially risky bank? I submit none. A free market likely would generate a “Consumer’s Report” for banks, and those willing to assume extra risk for their deposits would benefit from a higher interest. I for one would have more confidence in a privately managed bank rating system than a government one.

Allow me also to note that, in “Free to Choose”, Milton Friedman pointed out that the first bank to fail in the Great Depression, the Bank of the United States, paid depositors 97 cents on the dollar when it was unwound. Surely bill.com (and IMA) could survive such a haircut!

Thank you for your thoughtful articles.

Having created the conditions for massive inflation on both the fiscal and monetary side, the FED has made the mistake of trying to rapidly bring down inflation entirely on the monetary side (which is the only part they control) rather than being honest and saying – “We are going to have persistent inflation for a few years, yet we are going to restrict monetary policy somewhat to help bring inflation down.” It would be great of policy makers would stop pretending that if they just apply the right techniques we could avoid all economic pain. Even if government policies had been perfect there would still have been significant negative economic consequences from the pandemic.

The good news is that 10 year treasuries have already dropped 50 basis points in yield within the last month. This means that the unrealized losses on bank balance sheets has also declined. I don’t invest on my ability (more accurately – my lack of ability) to forecast interest rates, but it seems likely to me that both inflation and interest rates will be coming down by the end of this year. Regrettably, the reason for this is primarily that economic growth will be coming down (or negative) with a bit of a positive development in supply chains. I do think that you are spot on to point out that credit is going to be both tighter and more expensive for an extended period of time and this will contribute to slow growth.

The bad news is that it is difficult to see the U.S. federal government being willing to allow rising unemployment and all the problems that come with economic slowing to simply work through the system without implementing policies that recycle the current problem.

It is interesting to hear so many stock market pundits saying things like: “You should now be investing in companies with good balance sheets and strong cash flows.” What exactly were they investing in a year ago?

Thanks again!