January 2016

The article is very long. It is long for two reasons: first, it is was originally a two-part article that I folded into one; and second, I am dealing with the very complex topic of investing in today’s global economy. I wrote this article a year ago, and some themes like “be careful of MLPs” are not as relevant anymore, but overall it is still a very useful article for the world we face today.

“What the —- do I do now?” This was the actual subject line of an e-mail I received that really summed up most of the correspondence I got in response to an article I published last summer.

To be fair, I painted a fairly negative macro picture of the world, throwing around a lot of fancy words, like “fragile” and “constrained system.” I guess I finally figured out the three keys to successful storytelling: One, never say more than is necessary; two, leave the audience wanting more; and three …

Well, never mind No. 3, but here is more. Before I go further, if you believe the global economy is doing great and stocks are cheap, stop reading now; this column is not for you. I promise to write one for you at some point when stocks are cheap and the global economy is breathing well on its own — I just don’t know when that will be. But if you believe that stocks are expensive — even after the recent sell-off — and that a global economic time bomb is ticking because of unprecedented intervention by governments and central banks, then keep reading.

Today, after the stock market has gone straight up for five years, investors are faced with two extremes: Go into cash and wait for the market crash or a correction and then go all in at the bottom, or else ride this bull with both feet in the stirrups, but try to jump off before it rolls over on you, no matter how quickly that happens.

Of course, both options are really nonoptions. Tops and bottoms are only obvious in the rearview mirror. You may feel you can time the market, but I honestly don’t know anyone who has done it more than once and turned it into a process. Psychology — those little gears spinning but not quite meshing in your so-called mind — will drive you insane.

It is incredibly difficult to sit on cash while everyone around you is making money. After all, no one knows how much energy this steroid-maddened bull has left in him. This is not a naturally raised farm animal but a by-product of a Frankenstein-like experiment by the Fed. This cyclical market (note: not secular; short-term, not long-term) may end tomorrow or in five years.

Riding this bull is difficult because if you believe the market is overvalued and if you own a lot of overpriced stocks, then you are just hoping that greater fools will keep hopping on the bull, driving stock prices higher. More important, you have to believe that you are smarter than the other fools and will be able to hop off before them (very few manage this). Good luck with that — after all, the one looking for a greater fool will eventually find that fool by looking in the mirror.

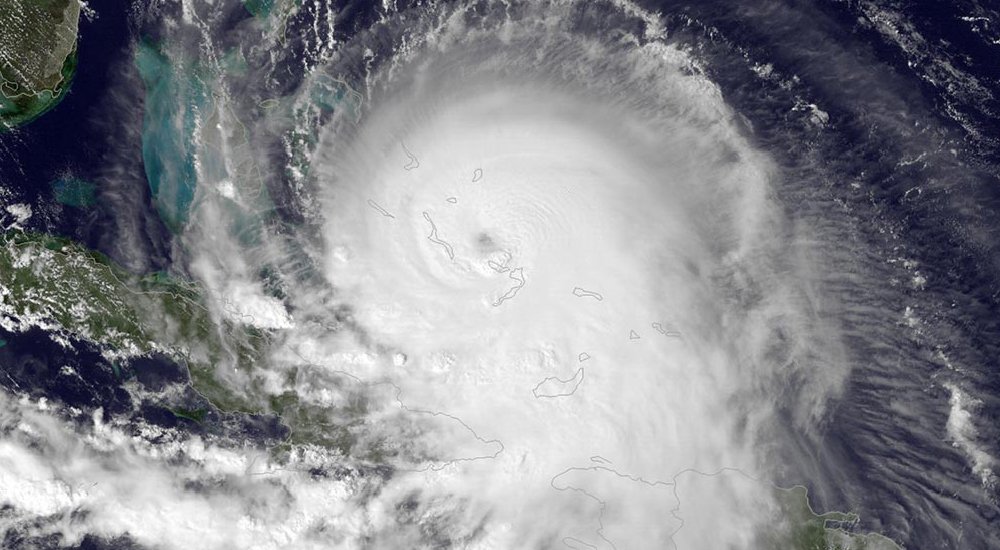

As I wrote in an article last spring, “As an investor you want to pay serious attention to ‘climate change’ — significant shifts in the global economy that can impact your portfolio.”

There are plenty of climate-changing risks around us — starting with the prospect of higher, maybe even much higher, interest rates — which might be triggered in any number of ways: the Fed withdrawing quantitative easing, the Fed losing control of interest rates and seeing them rise without its permission, Japanese debt blowing up.

Then we have the mother of all bubbles: the Chinese overconsumption of natural and financial resources bubble. Of course, Europe is relatively calm right now, but its structural problems are far from fixed. One way or another, the confluence of these factors will likely lead to slower economic growth and lower stock prices.

So “what the —-” is our strategy? Read on to find out.

I’ll explain what we’re doing with our portfolio, but first let me tell you a story. When I was a sophomore in college, I was taking five or six classes and had a full-time job and a full-time (more like overtime) girlfriend. I was approaching finals, I had to study for lots of tests and turn in assignments, and to make matters worse, I had procrastinated until the last minute.

I felt overwhelmed and paralyzed. I whined to my father about my predicament. His answer was simple: Break up my big problems into smaller ones and then figure out how to tackle each of those separately. It worked. I listed every assignment and exam, prioritizing them by due date and importance. Suddenly, my problems, which together looked insurmountable, one by one started to look conquerable. I endured a few sleepless nights, but I turned in every assignment, studied for every test and got decent grades.

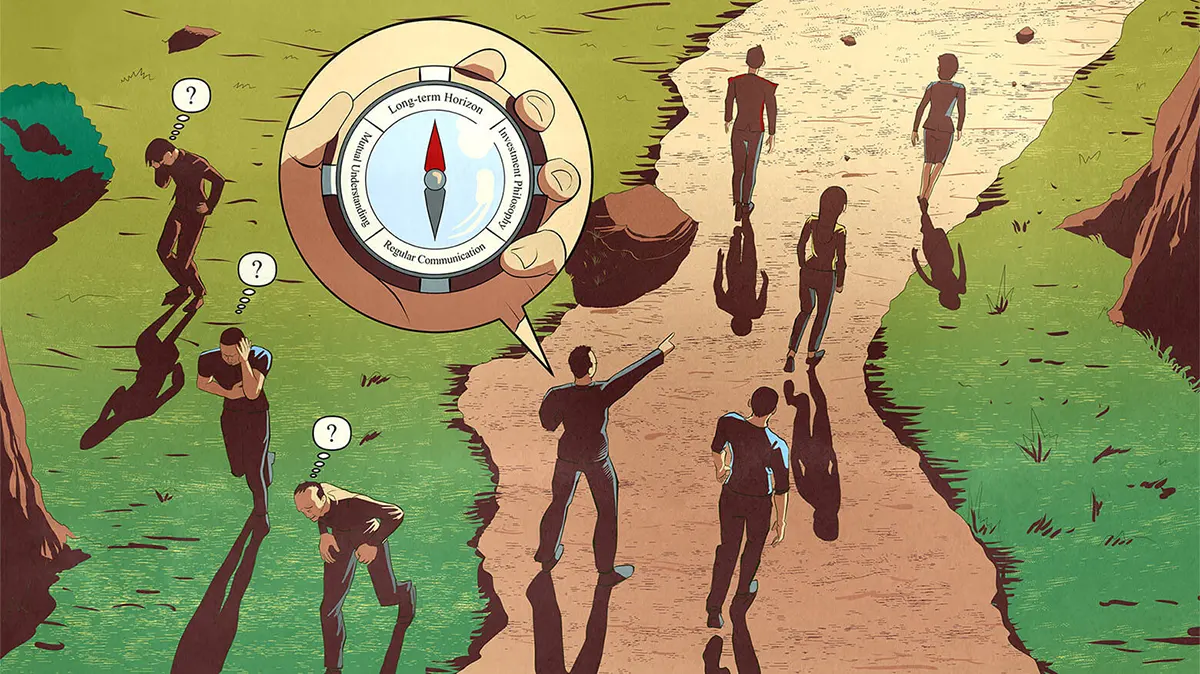

Investors need to break up the seemingly overwhelming problem of understanding the global economy and markets into a series of small ones, and that is exactly what we do with our research. The appreciation or depreciation of any stock (or stock market) can be explained mathematically by two variables: earnings and price-earnings ratio.

We take all the financial-climate-changing risks — rising interest rates, Japanese debt, the Chinese bubble, European structural problems — and analyze the impact they have on the Es and P/Es of every stock in our portfolio and any candidate we are considering.

Let me walk you through some practical applications of how we tackle climate-changing risks at my firm.

When China eventually blows up, companies that have exposure to hard commodities, directly or indirectly (think Caterpillar), will see their sales, margins and earnings severely impaired. Their P/Es will deflate as well, as the commodity supercycle that started in the early 2000s comes to an end.

Countries that export a lot of hard commodities to China will feel the aftershock of the Chinese bubble bursting. The obvious ones are the ABCs: Australia, Brazil and Canada. However, if China takes oil prices down with it, then Russia and the Middle East petroleum-exporting mono-economies that have little to offer but oil will suffer. Local and foreign banks that have exposure to those countries and companies that derive significant profits from those markets will likely see their earnings pressured. (German automakers that sell lots of cars to China are a good example.)

Japan is the most indebted first-world nation, but it borrows at rates that would make you think it was the least indebted country. As this party ends, we’ll probably see skyrocketing interest rates in Japan, a depreciating yen, significant Japanese inflation and, most likely, higher interest rates globally. Japan may end up being a wake-up call for debt investors.

The depreciating yen will further stress the Japan-China relationship as it undermines the Chinese low-cost advantage. So paradoxically, on top of inflation, Japan brings a risk of deflation as well. If you own companies that make trinkets, their earnings will be under assault.

Fixed-income investors running from Japanese bonds may find a temporary refuge in U.S. paper (driving our yields lower, at least at first) and in U.S. stocks. But it is hard to look at the future and not bet on significantly higher inflation and rising interest rates down the road.

A side note: Economic instability will likely lead to political instability. We are already seeing some manifestations of this in Russia. Waltzing into Ukraine is Vladimir Putin’s way of redirecting attention from the gradually faltering Russian economy to another shiny object — Ukraine. Just imagine how stable Russia and the Middle East will be if the recent decline in oil prices continues much further. Defense industry stocks may prove to be a good hedge against future global economic weakness.

Inflation and higher interest rates are two different risks, but both cause eventual deflation of P/Es. The impact on high-P/E stocks will be the most pronounced. I am generalizing, but high-P/E growth stocks are trading on expectations of future earnings that are years and years away. Those future earnings brought to the present (discounted) are a lot more valuable in a near-zero interest rate environment than when interest rates are high.

Think of high-P/E stocks as long-duration bonds: They get slaughtered when interest rates rise (yes, long-term bonds are not a place to be either). If you are paying for growth, you want to be really sure it comes, because that earnings growth will have to overcome eventual P/E compression.

Higher interest rates will have a significant linear impact on stocks that became bond substitutes. High-quality stocks that were bought indiscriminately for their dividend yield will go through substantial P/E compression. These stocks are purchased today out of desperation. Desperate people are not rational, and the herd mentality runs away with itself. When the herd heads for the exits, you don’t want to be standing in the doorway.

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) and master limited partnerships (MLPs) have a double-linear relationship with interest rates: Their P/Es were inflated because of an insatiable thirst for yield, and their earnings were inflated by low borrowing costs. These companies’ balance sheets consume a lot of debt, and though many of them were able to lock in low borrowing costs for a while, they can’t do so forever. Their earnings will be at risk.

As I write this, I keep thinking about Berkshire Hathaway vice chairman Charlie Munger’s remark at the company’s annual meeting in 2013, commenting on the then-current state of the global economy: “If you’re not confused, you don’t understand things very well.” A year later the state of the world is no clearer. This confusion Munger talked about means that we have very little clarity about the future and that as an investor you should position your portfolio for very different future economies. Inflation? Deflation? Maybe both? Or maybe deflation first and inflation second?

I keep coming back to Japan because it is further along in this experiment than the rest of the world. The Japanese real estate bubble burst, the government leveraged up as the corporate sector deleveraged, interest rates fell to near zero, and the economy stagnated for two decades. Now debt servicing requires a quarter of Japan’s tax receipts, while its interest rates are likely a small fraction of what they are going to be in the future; thus Japan is on the brink of massive inflation.

The U.S. could be on a similar trajectory. Let me explain why.

Government deleveraging follows one of three paths. The most blatant option is outright default, but because the U.S. borrows in its own currency, that will never happen here. (However, in Europe, where individual countries gave the keys to the printing press to the collective, the answer is less clear.) The second choice, austerity, is destimulating and deflationary to the economy in the short run and is unlikely to happen to any significant degree because cost-cutting will cost politicians their jobs. Last, we have the only true weapon government can and will use to deleverage: printing money. Money printing cheapens a currency — in other words, it brings on inflation.

In case of either inflation or deflation, you want to own companies that have pricing power — it will protect their earnings. Those companies will be able to pass higher costs to their customers during a time of inflation and maintain their prices during deflation.

On the one hand, inflation benefits companies with leveraged balance sheets because they’ll be paying off debt with inflated (cheaper) dollars. However, that benefit is offset by the likely higher interest rates these companies will have to pay on newly issued debt. Leverage is extremely dangerous during deflation because debt creates another fixed cost. Costs don’t shrink as fast as nominal revenues, so earnings decline. Therefore, unless your crystal ball is very clear and you have 100 percent certainty that inflation lies ahead, I’d err on the side of owning underleveraged companies rather than ones with significant debt.

A lot of growth that happened since 2000 has taken place at the expense of government balance sheets. It is borrowed, unsustainable growth that will have to be repaid through higher interest rates and rising tax rates, which in turn will work as growth decelerators.

This will have several consequences: First, it’s another reason for P/Es to shrink. Second, a lot of companies that are making their forecasts with normal GDP growth as the base for their revenue and earnings projections will likely be disappointed. And last, investors will need to look for companies whose revenues march to their own drummers and are not significantly linked to the health of the global or local economy.

The definition of “dogma” by irrefutable Wikipedia is “a principle or set of principles laid down by an authority as incontrovertibly true.” On the surface this is the most dogmatic columns I have ever written, but that was not my intention. I just laid out an analytical framework, a checklist against which we stress test stocks in our portfolio.

Despite my speaking ill of MLPs, we own an MLP. But unlike its comrades, it has a sustainable yield north of 10 percent and, more important, very little debt. Even if economic growth slows down or interest rates go up, the stock will still be undervalued — in other words, it has a significant margin of safety even if the future is less pleasant than the present.

There are five final bits of advice with which I want to leave you: First, step out of your comfort zone and expand your fishing pool to include companies outside the U.S. That will allow you to increase the quality of your portfolio without sacrificing growth characteristics or valuation. It will also provide currency diversification as an added bonus.

Second, disintermediate your buy and sell decisions. The difficulty of investing in an expensive market that is making new highs is that you’ll be selling stocks that hit your price targets. (If you don’t, you should.) Of course, selling stocks comes with a gift — cash. As this gift keeps on giving, your cash balance starts building up and creates pressure to buy. As parents tell their teenage kids, you don’t want to be pressured into decisions. In an overvalued market you don’t want to be pressured to buy; if you do, you’ll be making compromises and end up owning stocks that you’ll eventually regret.

Margin of safety, margin of safety, margin of safety — those are my last three bits of advice. In an environment in which the future of Es and P/Es is uncertain, you want to cure some of that uncertainty by demanding an extra margin of safety from stocks in your portfolio.

0 comments

0